Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

The 360 degree Olympic News Experience

!["I, Scientist" at TEDx Warwick [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/563face7e4b06c325c739ba9/1447019575958-NVZOYLTVWZ2QEWH1TPEM/image-asset.png)

"I, Scientist" at TEDx Warwick [VIDEO]

Can Twitter open up a new space for learning, teaching and thinking?

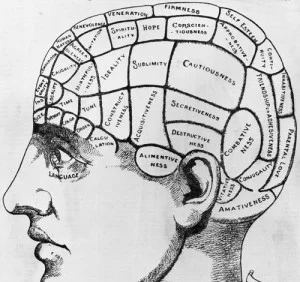

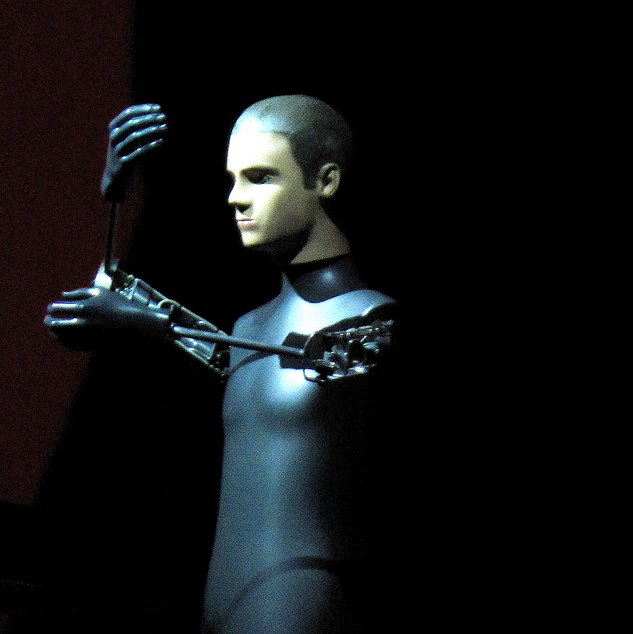

Justifying Human Enhancement: The Accumulation of Biocultural Capital (2013)

Google Glass Envy

Social Learning 2.0: A New Teaching Ethos for Universities

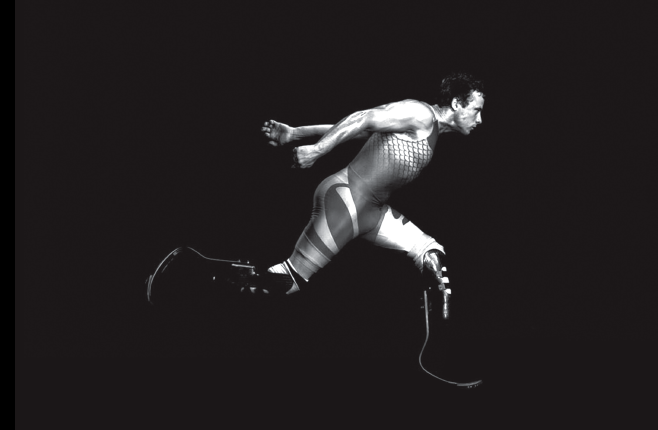

Oscar Pistorius granted bail

Oscar Pistorius is more than just a fallen hero

Why the doping problem is here to stay

Why Wasn't Lance Armstrong Caught Earlier?

De Morgen publishes my Lance Armstrong piece

My take on Lance Armstrong in Wired Magazine

TEDx Warwick

My secret article on Lance Armstrong

So Long, Lance. Next, 21st-Century Doping.

The A to Z of Social Media for Academia

It's not the end of the world, yet

#LoveHE + Love Social Media?

To Tweet, or Not to Tweet?