Make it stand out

What’s been happening?

Altmetric Annual Conference

Virtual Reality and Esports

Good Science Begins with Communication

News Media Coalition

The Journal of Future Robot Life

What is Transhumanism ?

Transhumanism @ BlueDot Festival

DRONES @ Microdot

Good Science Begins with Communication

Sheffield International Documentary Festival

Cheltenham Science Festival

Athlete 2.0

Gene Doping for Humanity

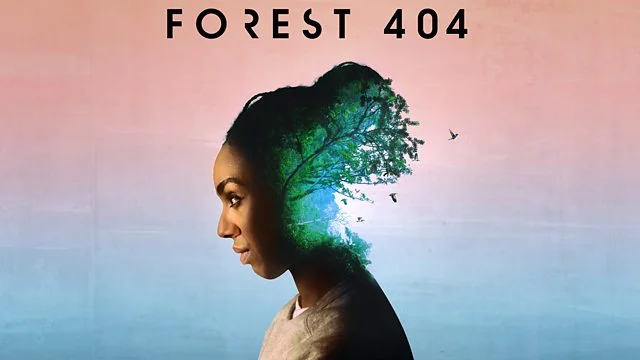

Forest 404 & Human Enhancement

Digital Health Generation 2019

The Royal Society and the Digital Society

E(merging) Technologies & The Ideas Economy

Sport 2.0 published in Japanese

Putting the NHS in Fortnite