Last November, I was asked to give a talk for a legal summit examining the doping dilemma in sport. It was a chance to reflect on 15 years of immersing myself in this complex subject. You can download the entire book publication from this event here but here's my manuscript pasted below for ease.

I. Overview of a Current Ethical Challenge in Anti-Doping, by Professor Andy Miah

Thank you to the WADA commentary team for inviting me here to give a talk. It has been a long journey for me in anti-doping and, to some extent, I want to take you through that 15 years or so within which I have often found myself on, for many people, the wrong side of the argument, for want of a better phrase. I was asked to talk about a current ethical issue around anti-doping. I think there are many, but I want to give you a glimpse of one particular topic through that journey that I have had in this world and outside of it. I began in this field from a sports science background. My PhD was in bioethics and sport, where I looked at genetics in particular, and my work expanded into bioethics more broadly. It is that interface between sport’s use of performance enhancement and the wider societal uses of technology that I want to address.

Forgive me reading a bit of the manuscript. Often I give talks just by talking, but I sometimes also write a manuscript that I develop through the talk. With this one I'm going to read a bit and hopefully give you an insight into the challenge, I think, with identifying what constitutes a current issue around ethical concerns in anti-doping.

Around 20 years ago I gave a talk at the first International Conference on Human Rights and Sport which took place in Sydney. I don't know if there was a second International Conference on Human Rights and Sport, but the issues were quite significant. My talk was titled, quite simply, “The Human Rights of the Genetically Modified Athlete”. Most people, as you can imagine thought: “What the hell is that about?” Especially people in sport thought this must be something like doping but just on a genetic level; that's how we should regard it and how we should think about the ethical issues around this topic. For most people in that world, this was simply another case of “bad hombres” using things they shouldn't be to compete in sport. But it was much deeper for me than just that. I was interested in thinking about a world in which there were genetically modified people whose enhancements were decided for them by the genetic selection or enhancement decisions of their parents or ancestors and how the world of sport might deal with that kind of person.

I wanted to imagine athletes who had not, themselves, done anything to achieve their genetic advantage but whose parents, who had sought to optimise their child’s chances through genetic selection or genetic enhancement, would have an impact on their lives. Their existence would not violate any rule within anti-doping, even though their being permitted to take part in elite sport would certainly mean that anyone who was not genetically modified or selected would be less competitive.

This was a time of considerable change in the world more broadly. This talk found itself one year before the completion of the Human Genome Project. I want to take you back to that moment.

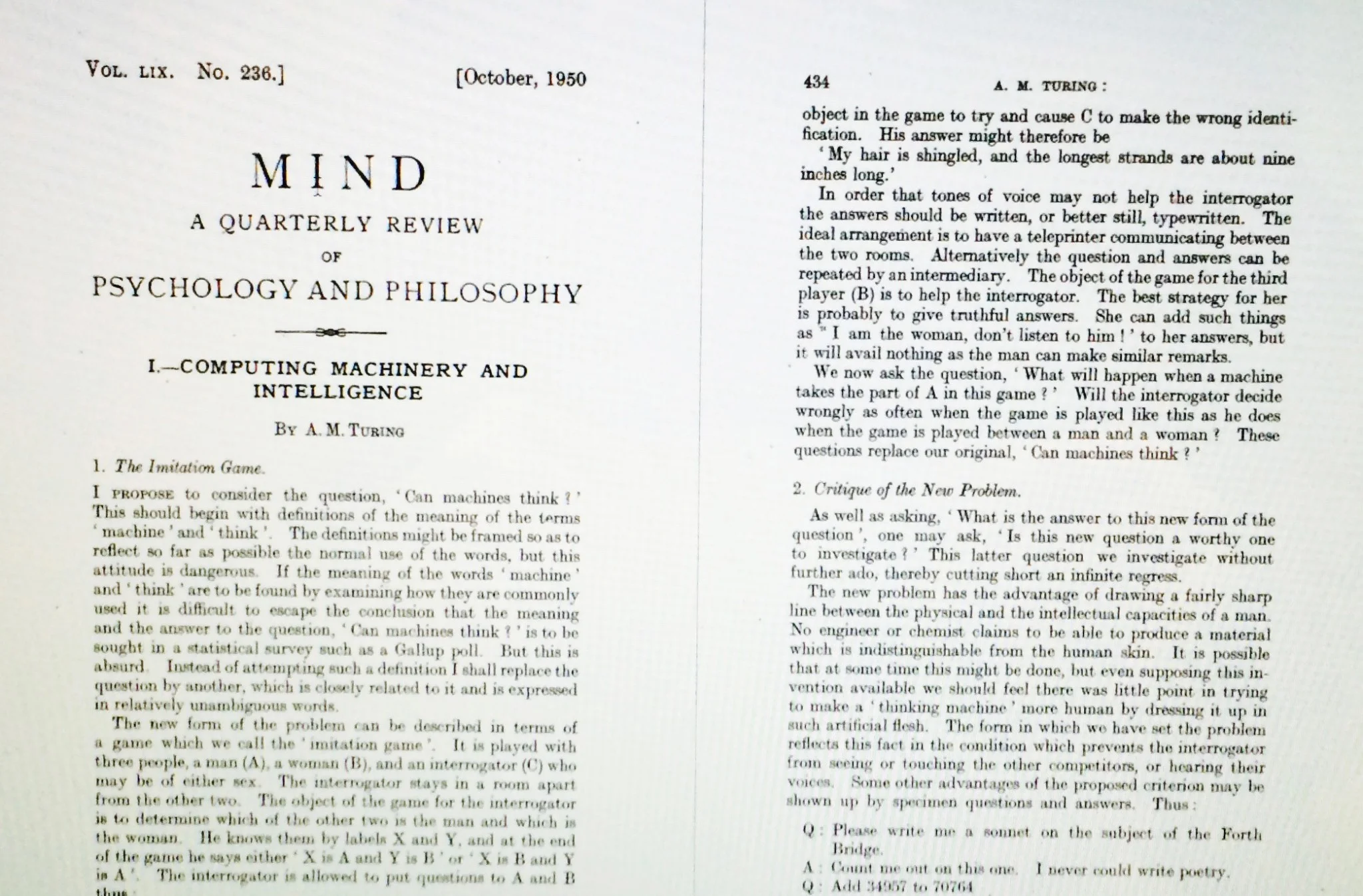

The Human Genome Project was nearing completion, and in fact was creating an incredibly challenging set of ethical issues for the world at large. It seemed to me particularly challenging for the world of sport. How will it deal with a world in which this technology was used? But all of a sudden the work of Crick, Watson and Franklin came to life. We found ourselves in the middle of a new era in human evolution. This was what was at stake at the time: this feeling that we are transcending those biological limits and remaking humanity in quite controversial and challenging ways. We hadn't figured out how this would operate. So I wondered how would the world of sport deal with an era where genetic information and even gene transfer found its way into sport.

Looking back, I suppose I also thought that this was a game-changer for the subject and that intrigued me, certainly. Gene doping was going to bring about the collapse of anti-doping, a system which I had studied and found to be left wanting philosophically and practically as a project interested in sustaining a moral framework to sport that I thought was unjustified, undesirable, and ineffective.

Now, some 20 years later, and also 20 years since New Scientist published its first article on performance genes, I'm left wondering: “Is this still a current issue?”

In 2001, in September that year, there was a conference scheduled at Cold Spring Harbor where the World Anti-Doping Agency would talk about gene doping and the prospects. 9/11 happened, that conference was cancelled and postponed to the following year, but this was the time at which Professor Lee Sweeney began to say that he was being contacted by athletes and their entourages with a view to them being enrolled into clinical trials using gene therapy. This brought the issue to life for the world. Lee Sweeney saying this made it a live issue, made it a current issue.

Lee's work on IGF-1 in particular revealed a proof of principle in the science and he spoke of an appetite among athletes to enroll within his trials. This was about as current as it got, or so I thought. Also at this time the IOC set up a gene therapy working group and soon after WADA did the same. We've now had a good 15 years of talking about this matter, but what has really changed? Well, we have research like this (indicating video of mouse on treadmill) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcXuKU_kfww coming out of Case Western Reserve University, which gives you a sense of how genetic interventions may have an impact on performance.

So over this 15 years or so there have been discoveries, findings, that suggest a proof of principle that could have applications for humans. And since every Olympic Games from Sydney onwards the media has published stories claiming that gene doping is the next big threat for sports while many other threats have also come and gone. Tthink of THG, the ‘clear’ or designer steroids more generally. And there have been examples of how genetic interventions can dramatically affect performance capacity, at least within animal models.

So it has been current for at least 15 years. Fast forward now to 2016 and we see how this becomes manifest within public discourse.

I was in a meeting with our chief science adviser in the British government this week where we talked about trust and expertise, and I gather it came up a little bit yesterday. But here's how it happens. Scientists were asked about what's going on in the world of science, and they tell them. They are then asked about what's going to come next, and they tell them again.

“We don’t know yet whether this has been done anywhere, but…it will be used sometime”

This is a quote from Carl Johan Sundberg [WADA Gene Doping Panel] from just last year, before the Olympic Games began in Rio, which tells you how this discourse is propagated within the media, how current issues are formed through the opinions of expertise but, crucially, through the requests of them to make predictions about what's coming next. So it is a discourse that's facilitated by experts. One of the predicaments, I think, of anti-doping not specifically, but it certainly is one that it needs to deal with, is the ethics of communication around emerging technology issues. It is a real challenge.

You can find quotes like these from every single Olympic Games period. Usually about a month before WADA puts out its big statements about the fact that no one is going to get away with it this time, we have some fancy new test that is going to catch everybody, which happened last year with a genetic test for EPO, and you have these claims about whether in fact gene doping is here and here to stay.

Personally I experienced this directly. In 2004, I published a book called Genetically Modified Athletes, and just before the Athens Olympic Games, the BBC asked me on to their flagship Newsnight programme to talk about these implications and we had a good debate about where we were and where it might go. Eight years later, during the London 2012 Games, I had exactly the same debate on the same television programme about gene doping. It was almost word for word. So there's a real challenge here in terms of how we think about what is current and how we deal with it.

If this is a current issue, what was it 20 years ago when I started writing about the subject, when New Scientist published its first article on the subject? What is the difference between an emerging technology and a current technology when thinking about what we should be doing within our ethical investigations and policy making?

Some of my learning in bioethics were shaped by time at the Hastings Center in New York, where conversations with Dr Thomas Murray, who was involved with WADA at various levels, led me to conclude that sport would not deal with this matter head on since bioethics, it is often said, must deal only with the present-day reality of scientific possibilities, not what might be here in five or ten years' time. Genetic enhancements weren't possible scientifically, at least we didn't know that they would work and be safe, and so did not deserve our time, even if they were rich philosophical debates. Instead we focused on gene tests and selection, and soon after such tests were becoming available. Here's one screen shot of a genetic test that was made available commercially. You could buy this test over the Internet. It simply takes a mouth swab and gives you some data on whether you are more likely to be a power-based on endurance-based athlete. Every scientist in this field has criticised this test, but the point, I think, from a policy perspective and from an intervention perspective is that it has become a social reality. The test is out there. The language of genetic tests as being determining of capacities or likely life achievements became a reality. So this led WADA to focus on genetic tests, and it published the Stockholm declaration in 2005, based on our talks.

Now I may have an erroneous definition of the word current, but it does matter how we define this term. I consider it essential to the work of ethics that we do mid to long-term speculative work. Space, time, and money is required to undertake such enquiries or else we lose sight of the bigger problems and lose time to determine our resolve. Failing to dialogue with speculative matters also limits the duration of our convictions and undermines our capacity to avoid problems that we may face in the future. In any case it is critical to distinguish between different forms of that word current. And we can have quite simple distinction between what is happening right now, so for example cases that come up in the world of sport or actual gene doping that's taking place that we know about, this is one way of thinking about what's current. But a lot of the conversation around anti-doping focuses on a second definition which talks about the sorts of things that preoccupy our time - the worries we have about the future. Certainly for nearly 20 years now, gene doping has been a "current" issue in that respect.

While it makes sense that we focus our efforts on the first of these, focusing on: Well, if it's not here yet, let's focus on the stuff that's here and deal with that. We need to think about the second one to avoid having to deal with the first one. If we don't deal with these longer-term implications, then we have a harder time dealing with the stuff that comes at us at crisis points.

Here's an example of the problem. We are moving into a world where these technologies are talked about not as a means of distorting nature or corrupting some internal essence or jeopardising a moral framework to how we recognise talent or effort in sport, and the like. Rather, it actually has something much deeper to do with how we are changing as a species and as individuals. This terribly long quote is a good indication of that.

A quote from Lee Sweeney's work, who I mentioned earlier, who has been working with WADA trying to find ways of detecting gene doping. But he says, and I'll read it out:

1. “From my own work with the mice, I also know that earlier you intervene, the better off you're going to be when you get old. So once you go down that path, I think it's unethical to withhold from someone something that would actually allow their muscles to be much healthier now and to the future. As long as there's no safety risk, I don't see why athletes should be punished because they're athletes. So I'm on the other side of the fence from Wada on this one, even though we're on the same team right now”

2. Lee Sweeney, Jan 2014

3.

At the moment the direction of travel for genetics is that, for it to be an effective public health intervention, we need to intervene before an athlete even becomes an athlete.

These technologies that, at the moment, are within the WADA Prohibited List and rejected by the sports community generally, are seen as kind of discrete doping problems, but they are part of a wider change in the circumstances of our biological condition.

A lot has happened over 20 years or so. We have now an article that covers gene doping within the WADA Code, even if our knowledge of what is taking place is limited. Over the years there have been indications of gene doping at Games but nothing confirmed. We've heard talk about specific genetic products being used at different Games; but, again, it is all very unclear. My concern is that the present strategy doesn't really address the problem that I wanted to consider back in Sydney in 1999, which was to do with the way in which genetics enters the population in a much deeper sense, perhaps through germ-line transfer of enhancements.

People in the world of sport, when asked this question about that germline modification or these wider questions about society and how it uses technology will shrug their shoulders and say, well, what can we do? We have nothing to do as a sporting organisation to address this. We have to see how society changes its values and, if it does, we may respond to it. Others will talk about it as just complete nonsense, that germ-line genetic engineering is just pie in the sky and akin to science fiction, and it is then also quickly dismissed. But then I'm often reminded, and have often been reminded over these years, as to how quickly these things change, how technology is taking us into new realms of capability. And year after year I have seen examples of that.

For example, this is from the TED Conference happening this week in Vancouver.

[IRON MAN TED VIDEO]

Sports find themselves at a time of tremendous change in the sorts of things that people want to do with their lives. Numbers around many sports, traditional sports, are diminishing. People are inventing alternative forms of physical practice which have alternative values and relationships to this problem of anti-doping.

One of the big areas that I wasn't going to get into but just to mention it very briefly is the rise of E-sports - competitive computer game playing - which has risen in the last few years significantly. It has so many profound implications for the world of sport. I could give a whole presentation on just that. However, the key thing here is that sport is losing generations to other kinds of activities, where the approach to the questions of doping is very different. So, we need to look at these and understand really what is going on and where it leaves us with regard to the ethical dilemmas that sports face.

In that context, the second the act of this talk is to men tion a few examples. Just to give you a glimpse of some of these challenges that we face

The first one I want to talk about is CRISPR, this technology that will allow a much more sophisticated approach to gene editing. CRISPR has been discussed at length in the press in the last couple of years, where there is concern that, in factk that era of gene transfer for potential enhancements that was dismissed 15 years ago as pie in the sky, as not quite here yet, is around the corner. The quotes again from scientists working in this field will say that this is easy to do, it may not be safe, but this is something that is now within our grasp. We also have projects that are changing those capacities we have as people. One of the nicest examples, I think, is North Sense. Here's a quick glimpse of it.

[VIDEO PLAYED]

Now, many nonhuman animals have a capacity to know which direction is north, and this project is giving humans this sensorial capacity, which can change the sorts of things we can do in our lives. My proposition to you is that, in fact, this describes the future of sport much more than the older problems of doping that we see played out in the world of sport today. Creating people with different functions, different capacities, will lead to the creation of different kinds of sports and we'll see how this will change that approach that we have to the doping problem.

We also have the rise of ingestible sensors. A patent was awarded for this for the first time a year ago in the US, and we now begin to see this technology being rolled out. Here is, again, a sense of how it works.

[PROTEUS VIDEO PLAYS]

This is here now. You can see how athletes might wish to use something like this to fine-tune their doping to avoid detection and so on, but you can also see how, perhaps, it can be used in a much wider sense as well.

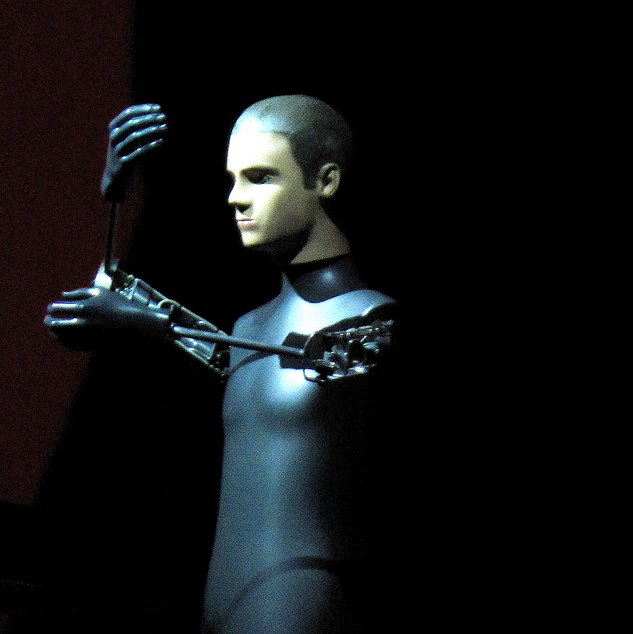

The next one is prosthetics. Prosthetics are changing the sense of what biology can do by transforming it into artificial apparatus. We saw this around the London 2012 Games with Oscar Pistorius, who became the first person to complete in an Olympic Games with a prosthetic device. But it was really only the beginning of this and we see ourselves at the cusp of an era where prosthetic devices on both significant levels like an artificial limb, but also on nanoscale levels, can be transforming that boundary between nature and technology to the point where it makes no sense to think about these as separate things.

So in different ways, each of these examples, I think is a problem for sport as they are not really covered by the Code not even its catch-all article which indicates the capacity to encompass other forms of enhancements that aren't listed specifically. But the Code fails the concern that medicine is slipping into the realm of enhancement rather than therapy, calling into question the role of medicine. Many people who work in this field coming from the medical perspective are worried this enhancement era transforms the act of providing medical care in a way that undermines it and so are pushing back against it. Yet, we exist in a world where we are increasingly comfortable with this slip and where some even argue that we have moved into a post-human era where the conventional assumptions about healthcare are no longer relevant.

I mentioned one example at breakfast this morning where, in the UK the NHS, our National Health Care Service, is beginning to experiment with artificial intelligence as a diagnostic tool within primary care. So you can see how these technological changes are coming. The dilemma, I think, to go back to the task I was set today, which was to talk about a current dilemma, can be articulated thus. How can anti-doping protect its social mandate, when human enhancement is allowing the general public to become more capable of performing acts of physical endeavour than the anti-doping compliant athlete?

The point at which the general public is more enhanced than the athlete is the point at which anti-doping becomes a failed project. As you will anticipate, I don't think that anti-doping can succeed, and what we will see steadily is an erosion of public interest in the unenhanced athlete and the expansion of alternative sports that will not operate by the same kinds of rules.

The answer, however, I think is found within the Code, which has a fundamental flaw within it. The Code is somewhat tautologous; it is a very self-contained set of directives and principles, self-referential in many ways. It asks the signatories to protect doping-free sport because that is the rule. It does not allow the signatories to question the rule. Even more worrisome is that within Article 18 on Education, it does not seek to undertake education in any meaningful sense.

As an educator myself my role is to guide students in the pursuit of certain ideas but to allow them to arrive at their own conclusions.

Anti-doping prescribes the end point of that educative route and it is to be in the service of the Code's purpose. In my view that is far from being education.

Thank you very much.

PROFESSOR KAMBER: Thank you, Andy, for your talk. I always enjoy your talks very much. I remember the first talks about gene doping and then we were on the brink, everybody is telling gene doping is around the corner, but I don't think so. But I'm convinced that we have to discuss this technical enhancement, these products helping people. But I think it is not a problem because we already have it in sports. We have all the sports equipment, already you have the bobsleigh, you have the Formula One cars. And so I think this direction is not such a problem. But I guess the discussion about gene doping, changing your genes, is over. I'm not sure it's coming to the sport. Because if you look at medical enhancement, medical improvement, in the last years, it didn't exist. But I agree with you that we have to discuss these enhancements with the technique, with this equipment we have. Maybe we have mixed races, as we have shown. This we have to discuss but no longer gene doping.

PROFESSOR MIAH: Wow, I can't believe you said that, Matthias, really. I'm staggered! I am given, you know that this is something that experts from your position say at every Olympic Games: This is something we need to discuss. It seems it is part of maybe it is part of the rhetoric. Maybe I misunderstand this. Is it simply about generating a sense of the fact that WADA is doing something, we're forward thinking, we're thinking about these problems and making clear to the public that this is what we're doing. But at every year over the last 15 years people within WADA have said: This is a problem we have to deal with. And the funding going into from their side, but also our side of it, suggests this is a serious concern. So I am surprised that you would say this, but I accept what you have said about the fact that gene therapy hasn't been particularly effective or successful in any medical sense, and the assumption is that until it is at least effective in a medical sense we wouldn't even dream of using it in a non-therapeutic context.

The caveat to that is there is no capacity to embrace its use within a non-therapeutic purpose because, as with other medical devices or methods or treatments, the limits of their regulation is in the precise terms of that therapeutic application. So, by implication, anything used out with those terms is considered to be unethical and unreasonable for scientists to be involved with. But the reason to put Lee Sweeney's quote up there is to show that people working within this field regard that the effective use of these next-generation therapies requires stepping back from the idea that there is something called "the natural course of aging" and intervene much earlier in life to benefit from those interventions later in life. When you get into that, for me that is a completely radical point for many people who think that, no, we get old and we die, and that's it. We might do some fixing along the way with some medicine, but the direction of travel for the project of western medicine [PAUSE] I was going to say "is immortality", but the less radical way to put that is this ongoing pursuit of interventions. And hopefully these interventions will be safer, but they need to happen earlier in life rather than later. You don't get to 70 and then start your gene therapy to deal with the problems you face, it has to be earlier on, and that is a big shift, I think, in how people will feel about it.

Sorry, that was a long response.

PROFESSOR SANDS: One more question and then we'll break to our panel. Right at the front over here.

JEAN-PIERRE MORAND: I must say that when we are listening to you it is like an abyss is opening in front of us. My reflection was the following. Sport is one aspect of life. What you are showing is touching on many, many, many more severe and more serious aspects, including who is going to be mortal, etcetera, etcetera. Then you say the Code is a failure. But I say, looking at this, sport as a concept becomes a failure. Because sport is based on comparison of people who are more or less having an equal field, otherwise it loses completely its function and sense and a competition will like a technical fair: which is the best matching? Which was designed the best by the best genetician then, and this is our product. There I think therefore doping becomes a detail and irrelevant in such a big, vast array of ethical problems.

PROFESSOR MIAH: I'm more optimistic.

I think that even with these technological interventions the human role in performance remains crucial and it is our task to decide which things are relevant to the test of competition and which things are not.

One of the central points of the presentation, and I was trying to draw attention to this mindful of the purpose of this event, is that there is no mechanism for that interface between sport and society within the Code itself.

Now that might be straightforward to many people. The Code is supported by governments and other organisations and their support implies a kind of assumption that this is what we want to do. But there needs to be an interface where people are able to discuss the ideology and the values behind it. And this is especially concerning when, within the Article 18 that talks about education, there is no statement about creating or nurturing critically-engaged athletes who can defend their position and understand what it is that matters to them about doping. It is entirely, I mean, for want of a better word, propagandist in how it approaches the concept of education. Without that interface within the Code, without some provision for a dialogue interface within that Code, it is destined to fail, I think. It doesn't fail, sport kind of happens and it takes place reasonably well, although we have these problems with it, but I do think the key point is that interface. At the moment the Code is pretty self-contained and it is about sport deciding what it wants to do and society accepting it. We need to look more broadly, I think.

PROFESSOR SANDS: Andy, a big thanks from the entire audience and from me. I think we take a moment to thank Andy for his very interesting and challenging outline of issues that we have faced and that we will face.

Andy, thanks a lot.

PROFESSOR MIAH: Thank you.